The Chicago Musical Extravaganza is Alive and Well in Las Vegas

The American musical extravaganza, begot in Chicago over thirteen decades ago, is alive and well in Las Vegas, Nevada; not that anyone in Chicago is aware of their City’s cultural history. At the dawn of the nineteenth century’s Gilded Age, a Chicago theater producer created a musical extravaganza, Arabian Nights, inspired by Christmas pantos he had witnessed as a child in England. It became a sensation! A local theater critic described the special effects: “the scene suddenly changes to the Dismal Swamp, and some marvelous mechanical effects are shown, the most novel of which is the steam curtain. The incantation of the magician is followed by a sight which is quite startling in its beauty. A cloud of vapor rises from the footlights to the proscenium arch, completely obscuring the view behind. On the vapor is thrown colored light.” The New York Times sent a reported and he was equally bedazzled, exclaiming: “doubtful if any spectacle has ever been given in the United States more magnificently.” While they were dazzled by the spectacle, they really couldn’t discern a story or a plot and didn’t much care. They didn’t need to be enlightened to be entertained.

Now a new musical extravaganza, Awakening, has opened in Las Vegas and the reviews read very similar to the Chicago original thirteen decades earlier. The reviewer for the local Vegas newspaper wrote: “I tried to figure out the message of the show. What’s the story here? About halfway through I just gave up. I was happy to watch the blue-costumed performers vault to the sky from their magic teeter-totters. I walked away stunned, impressed at what these artists had achieved. It didn’t matter that a lot of it went over my head, metaphorically and for real.” The megalomania of David Henderson’s Chicago musical extravaganzas has been captured by the producers of Awakening at Wynn’s Theater in Las Vegas. If you ever wondered what they were like, you will have to go to Nevada because they are completely forgotten in Chicago.

Is Covid to be the Death of Chicago’s Theater Community?

published summer 2020

The little Mercury Theater should have been a harbinger of what could happen on a large scale if nothing is to be done to save Chicago’s smaller commercial and neighborhood theaters. They were designated non-essential and may prove to also be perishable. The lessons of history are not reassuring. Before the pandemic of 1918 and the First World War 1917 to 1919, Chicago had a thriving and diverse commercial theater industry. There were dozens of theater companies traveling across America and almost as many were staged in Chicago as New York. In the first two decades of the twentieth century many of the most popular musical comedies and comic operas originated in Chicago. When the pandemic and the War was over, there were no commercial theater producers remaining in Chicago. Only the variety theaters survived and they would persevere only a few years into the Roaring Twenties.

Yet history also offers a possible solution. One of the largest components of commercial theater before the pandemic of 1918 was summer tent theater or “the straw hat circuit,” as it came to be known because men of the era preferred straw hats as part of their summer haberdashery. In 1910 the trade paper, Variety, estimated that there were about 300 shows playing in tents in the heartland, many of which were Chicago originated. Chicago’s amusement parks, such as White City and Riverview Park, included tent shows of music and comedy while the fine arts community usually left the heat and miasma of the city during the summer for rural Illinois where they produced the Greek classics under the stars. It offered the mosquitoes a rare opportunity for blue-blood.

If people are willing to eat and drink outside with social distancing, why would they not be willing to consume stage entertainment under the same circumstances? Millennium Park has two side tents both of which at thirty percent capacity would still equal a sold out show at most of the neighborhood theaters and the Pritzker Pavilion is massive and at even ten percent of capacity would accommodate a larger crowd than any indoor theater used by Chicago theater companies. In neighboring Grant Park is the still extent Petrillo Pavilion another massive capacity venue. Large tents could have been erected in the interior parks to accommodate all the theater companies for at least four or five months.

Nothing was done, the stage is dark and a year will pass. Can a theater community survive that long with no revenue? It seems Chicago’s leadership is confident that it can because nothing has been done to abet its survival.

Stagestruck at the Newberry Library

published 2015

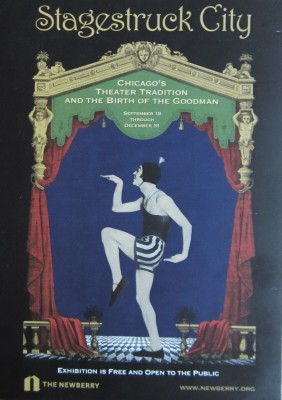

The Newberry Library has opened a new exhibition free to the public entitled: Stagestruck City, Chicago’s Theater Tradition and the birth of the Goodman. If viewing cultural artifacts of Chicago’s past cultural achievements is something you enjoy, then the Newberry exhibition has much to offer. The Newberry has a collection of very rare theater posters and artifacts from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The posters were advertisements for long since forgotten theaters such as Hooley’s and Haverly’s. Some of the posters are so fragile that they can only be illuminated in low light which is why the exhibition room looks closed for viewing. However, if it is Chicago’s theater traditions that lures you to the Newberry, then you will not likely learn much of Chicago theater history which is itself a facet of Chicago’s theater traditions: ignorance of its history.

The descriptions that accompany the artifacts are full of errors. For example, the description for the Sultan of Sulu, the first big musical hit of the twentieth century that started in Chicago, claims John T. McCutcheon wrote the music; yet the sheet music cover in plain sight clearly shows Alfred Walthall as the composer. The description for the Wizard of Oz, another Chicago begot monster musical, lists Frank Baum as the author and Paul Tietjens as the composer. In fact, Baum tried unsuccessfully to convert his children’s book into a musical so he sold the rights to Chicago producer Fred R. Hamlin who rewrote the book and discarded most of Tietjens’ music. Baum never complained as he made far more in royalties from the play than he had from his book.

The Newberry curator of this exhibition seems to adhere to the tradition that a “hit” play is one that has been a success on Broadway which also happens to be the criterion used by New York theater historians. While the Sultan of Sulu and the Wizard of Oz both were hits on Broadway, in this era there were many Chicago theater productions that were commercially successful with tours that lasted for years and yet they never played in New York. Chicago producer Lincoln J. Carter had plays on the “blood and thunder” circuit that toured for years in America and parts of Europe as did such original Chicago musical comedies as Louisiana Lou.

The central subject of this exhibition is the Goodman Theater which began ninety years ago this October and has grown into one of Chicago’s most esteemed cultural institutions. The purpose of the posters, maps, books and descriptions is to give context to the theater scene of Chicago in which the Goodman would assume its place. But the omissions and inclusions in the exhibition leaves an ambiguous impression. The Goodman then and now is an endowed theater. It is an institution of the fine arts not the popular arts. The exhibition does include information on the Little Theater movement and the Drama League which are part of Chicago’s fine art’s history but it also included a section on Robert L. Mott’s Pekin Theater, the deemed first black owned and operated theater in America. But worse, it coupled Mott’s theater to the 1915 movie the Birth of the Nation which was based on the novel the Klansman and glorified the KKK. Yet Mott was dead by 1915 and his theater gone.

Robert L. Mott is himself worthy of an exhibition if you can find enough still existing information. Why Mott was included in this exhibition while other notable Chicago producers were excluded doesn’t seem clear but whatever the case, this exhibition provides a very small aspect of a much larger story, Chicago;s theater history.

Stagestruck City is composed entirely of artifacts from the Newberry’s collection which simply isn’t broad and deep enough to provide a full overview of Chicago’s theater history. Chicago has always lacked a central depository and reference library for its popular culture. The Chicago History Museum which would seem the logical custodian; yet they have a surprisingly small collection. The Harold Washington Library of the Chicago Public Library System hosted a similar Chicago theater history exhibition with artifacts from their collection several years ago but they are missing much as well. The University of Illinois at Chicago library also has a small collection of Chicago theater artifacts. Yet much of what remains, is in collections outside of Illinois. The Library of Congress has a collection of posters from Chicago and the Theater Museum of America in Waterloo, Iowa has a collection of Lincoln J. Carter theater artifacts. Many of the actual script books of Chicago plays that were highly popular a century ago are scattered across America in university libraries.

No Chicago-based institution has sufficient resources to adequately address the subject of Chicago’s theater history in all its genres. The major issue ignored in the subject of Chicago’s theater traditions is why did Chicago’s theater industry collapse?